Organic Synthesis and Sustainability

Raising the bar in organic synthesis: at what cost to the environment?

As the expression goes, times have changed, and this is certainly true for organic synthesis. Years ago, there was little attention paid to the amounts of organic waste being created in the lab, or the costs associated with its disposal. How such waste is handled was rarely, if ever, discussed …unless it impacted our daily lives. That these issues would eventually become important topics was already foreshadowed in the forms of, e.g.,“atom economy”, and “step economy. ”The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry" followed soon thereafter, all having been introduced to the community even before the arrival of the current millennium. But as the world today has begun to take notice; we have all become increasingly aware that the practice of organic chemistry is having a major detrimental impact on the environment. It is absolutely clear that the manner in which organic chemistry is traditionally carried out must change; as is, it is not sustainable.

Since most (>80%) organic waste created by the chemical enterprise is attributable to organic solvents, many originating from our petroleum reserves (a finite resource), it is long past due for the “switch” to be made, a la nature, to a water-based discipline. This is the norm in the field of biocatalysis, so why has modern chemical synthesis, still only ca.200 years old, failed to make this connection; to do chemistry as nature has done for millions of years?

In recognition of the inevitable switch that must take place, whether truly for sustainability reasons, or otherwise (e.g., economics, that always favor greener processes; regulatory requirements, such as now seen in Europe under REACH; responses to environmental disasters that release toxic materials into drinking water and lands used for food production; etc.), we continue to devote most of our research program to developing alternative technologies that address the three key parameters associated with research today in organic synthesis: (1) the choice of reaction solvent; (2) the oftentimes required investment of energy in the form of heating or cooling reactions, and (3) the typical use of transition metal catalysts, many of which are endangered, in the 1-5 mol % range; this is 1-2 orders of magnitude greater than the ppm levels at which nature does catalysis. Every new reagent and every new methodology to be developed in the group must adequately address the question: If successful, what is the cost to the environment?

Designer Surfactants

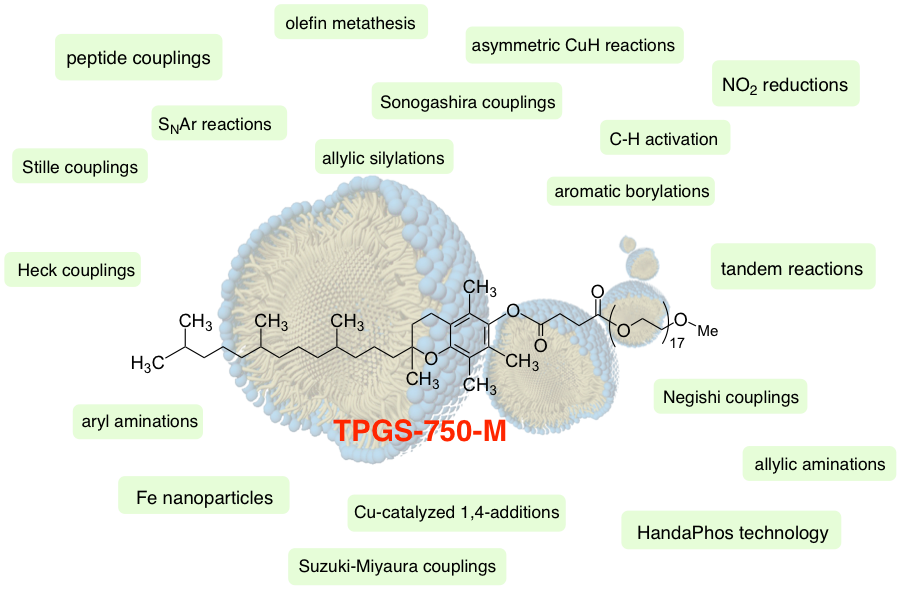

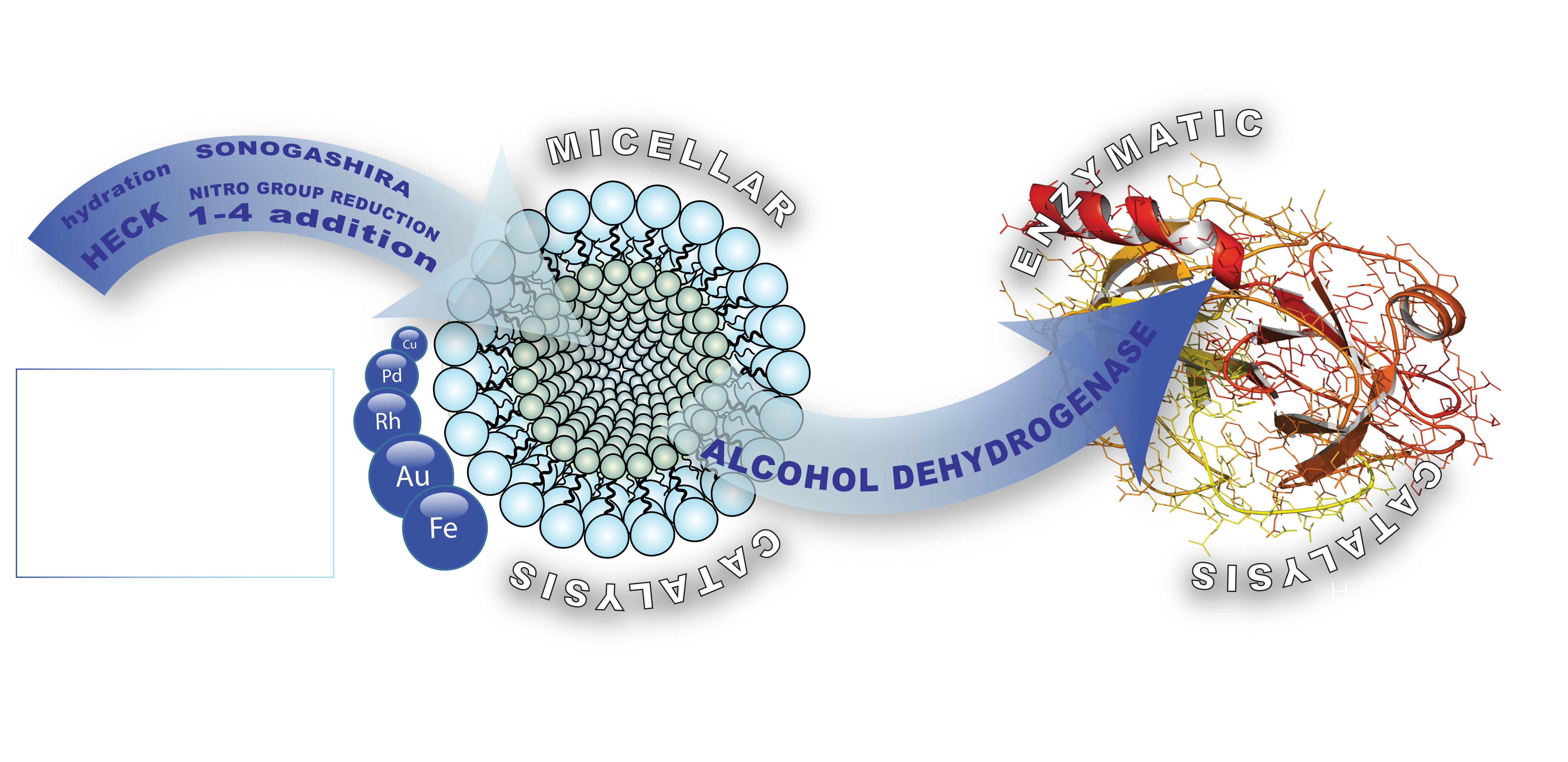

Our research in organic synthesis, therefore, is highly focused on the use of water as the gross reaction medium (and not the solvent). A solution to the issues associated with the insolubility of reaction substrates, reagents, catalysts, and additives, takes advantage of the well-known area of aqueous micellar catalysis. Here, very limited quantities, typically only two weight percent, of a “tailor-made” nonionic surfactant are enough to spontaneously self-aggregate in water to provide nanoreactors in which the reactions take place.

Amphiphiles specifically engineered to be of the correct size and shape for this purpose including TPGS-750-M and Nok, and most recently, Savie, are illustrated on the right (top). These are composed of environmentally acceptable materials, as each is prepared from a dietary supplement; the former is made from racemic vitamin E (an antioxidant), or phytosterols that are used to lower one’s level of LDLs (i.e., “bad”cholesterol). They individually enable a growing library of transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions to be performed in water under mild conditions. Nonetheless, a series of new amphiphiles has been designed for specific uses in synthesis, illustrated on the right (bottom). The first, MC-1, is especially effective in peptide synthesis. Highly functionalized and oftentimes polar, protected amino acids and peptides has given rise to a need for a modified micellar inner core, in this case a sulfone being introduced at a strategic location along the lipophilic chain so as to mimic DMSO. This newly designed surfactant enhances formation of all types of polypeptides in water at rt, without the need of a co-solvent. The other new surfactant, Coolade, offers a solution to reactions involving gas evolution that can lead to undesirable frothing. The technical issues inherent to gas-evolving reactions in surfactant solutions have been considerably minimized.

A sampling of the numerous types of reactions that can now be run in water under very mild conditions (rt – 45 °C) is shown down this page. It is worthy of note that while most of these may bear no relationship to each other, they can all be effected in the same reaction medium: water. And as a bonus, there is essentially no workup associated with these technologies. That is, while use of an organic reaction solvent is usually followed by an aqueous extraction with a different extraction solvent, then washing with brine, thereby creating enormous amounts of waste solvent and waste water streams, chemistry in water typically avoids these otherwise environmentally egregious protocols. For reactions now performed in water, either solid products are filtered (while the aqueous mixtures are recycled), or the aqueous mixtures are extracted “in flask” by simply adding a single organic solvent followed by its removal, now containing the organic, water-insoluble product. Hence, the oftentimes-heard argument against water-based chemistry that equal amounts of waste water are being created and that handling of organic solvent waste may actually be easier and less costly has no basis in reality using this micellar chemistry. In fact, several direct comparisons, presented in a review article, document that at least an order of magnitude less waste, both organic and water-based, is to be expected based on these technologies.

Reviews

Several reviews, beginning in 2008, most of which were invited, covering advances made over the past decade can be found below:

Aldrichimica Acta, 2008, 41, 59; Aldrichimica Acta, 2012, 45, 3; Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 10911; Green Chem. 2014, 16, 3660; ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 5838; J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 2806; Chem Eur. J. 2018, 24, 6672; Chemistry Today, 2020, 38, 6; Chem. Sci., 2021, 12, 4237; Synlett 2021, 32, 1588; Curr. Opin. Green. Sus. Chem., 2022, 38, 100686; Chem. Rev., 2023, 123, 5262–5296; Green Chem. 2023

In addition, shorter discussions addressing specific aspects of this new approach to synthetic chemistry in water are also available. These cover topics such as (a) What are the new rules under which chemistry in an aqueous micellar media now operates, and how can we take advantage of these?; (b) What is the “nano-to-nano” effect and how can this be used for heterogeneous catalysis in water?; (c) How has one prominent organic/inorganic chemist responded to an Opinion on the future of organic synthesis in water? (d) And what about the future of organic chemistry; Are we on "borrowed time"?

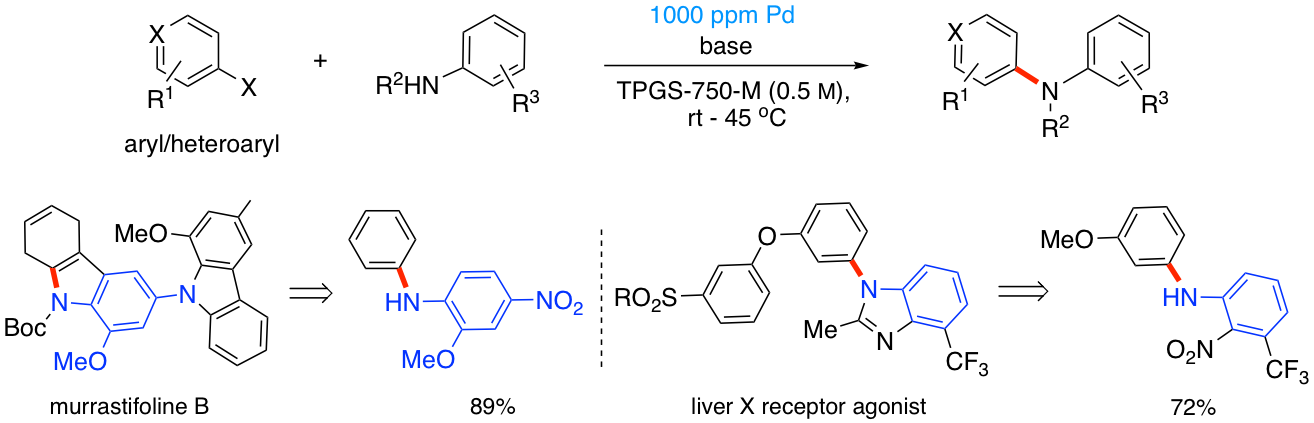

Pd-Catalyzed Aminations at the ppm level of metal

As part of our efforts to develop sustainable transition metal-catalyzed technologies, we have recently begun to focus on providing a new ligand for Pd-catalyzed aminations that can be effected in water under mild conditions and at the 1000 ppm level of metal invested. Our initial focus is on aminations utlizing aniline and aniline-like partners, together with aromatic and heteroaromatic halides. Biaryls that can be made using this enabling micellar catalysis technology include the pharmaceutiucally relevant cases shown below.

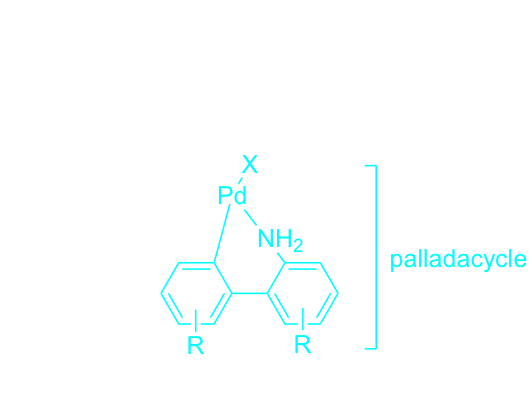

HandaPhos palladacycle

A newly designed palladacycle containing the ligand HandaPhos is being developed for use in Suzuki-Miyaura couplings in water under mild conditions, where the loading for Pd in this 1:1 complex is only 300-500 ppm. Several examples are already in hand, with the couplings taking place in nanoreactors composed of the designer surfactant TPGS-750-M. Using this new technology, products such as those shown below are readily prepared. At these low levels of Pd usage, residual metal in the isolated products has yet to exceed the FDA-allowed limit of 10 ppm.

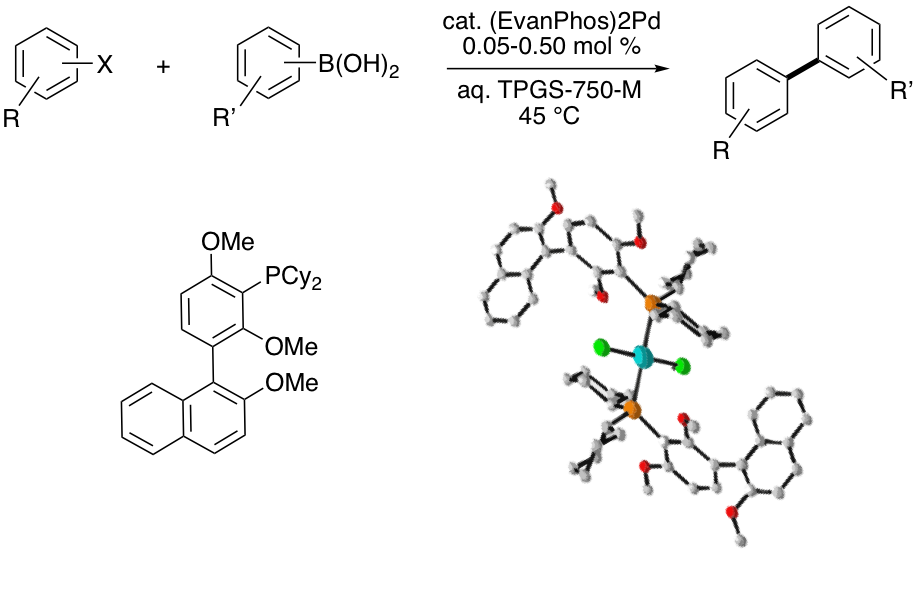

EvanPhos and beyond: A new ligand scaffold for ppm Pd catalysis

We are actively pursuing syntheses of novel biaryl mono-phosphine ligands for palladium-catalyzed coupling reactions. The first-generation ligand EvanPhos, prepared in only 2-steps from readily available materials, takes a new approach to the biaryl framework by placing the biaryl bond meta to the phosphine vs. the typical ortho-biaryl construction. This ligand features extended bench stability in both its free and Pd-complexed state, and is highly active as its Pd complex towards challenging coupling partners at 0.05-0.5 mol % (500-5000 ppm) catalyst loadings, used under mild aqueous conditions. We are currently investigating the corresponding palladacycle derivatives containing this catalyst, as well as analogues of this powerful ligand architecture to achieve truly green and sustainable catalytic systems.

EvanPhos palladacycle pre-catalyst

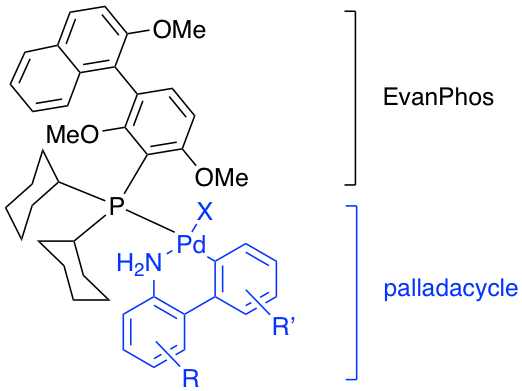

The facility with which EvanPhos can be prepared and the effectiveness of this ligand for ppm level Suzuki-Miyaura couplings suggested that the corresponding palladacycle might be an excellent, and convenient, pre-catalyst for use at the ppm level of Pd. Thus, a series of substituted palladacycles (i.e., with R and R’, see on the right) is currently being made to determine which ultimately affords the highest activity for use under aqueous micellar catalysis conditions.

Next generation ligand for Pd and Au catalysis at the ppm level

A next generation ligand following our disclosure of EvanPhos is underway, looking to achieve even greater reactivity associated with its derived 1:1 complex of palladium for general ppm level catalysis. Preliminary results look very encouraging, in particular where the naphthyl ring is more highly substituted (see R and R’, on the right), leading to Suzuki-Miyaura cross-couplings with aryl/heteroaryl bromides that require only 1000 ppm of Pd, done in water at 45 °C. Remarkably, this new ligand/Pd complex appears to be amenable as well to catalyzing reactions of aryl chloridesunder similar conditions, with only 2500 ppm (0.25 mol %) Pd. Extensions, as with HandaPhos technology (vide supra) to uses with other metals, such as gold, also look quite promising.

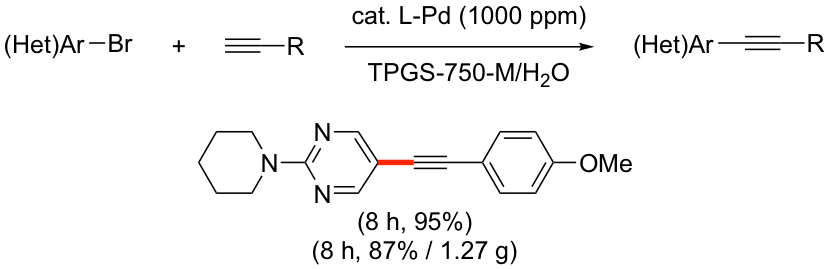

New technologies for Sonogashira couplings in water at the ppm level of Pd

The copper-free Sonogashira reaction is yet another highly valued and useful type of coupling that is Pd-catalyzed. Although we have previously shown that these can be smoothly run in water at rt, the level of Pd required at that time was too high (1 mol % or 10,000 ppm), given the endangered status of the platinoids. Hence, we are developing a new protocol that allows for 1000 ppm loadings of Pd derived from readily available, commercial sources of catalysts and ligands, enabled by aqueous micellar catalysis. Targets, such as that shown below, can be run at the gram scale.

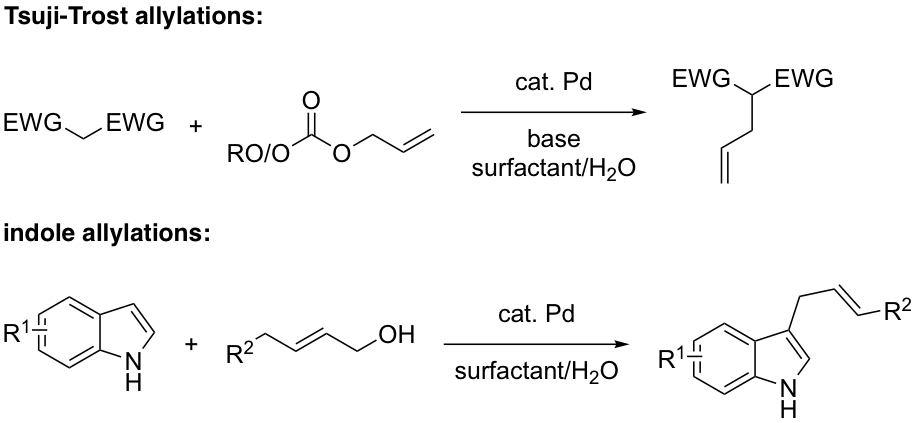

Pd-Catalyzed Tsuji-Trost reactions at the ppm level of metal

Tsuji-Trost reactions are another type of Pd-catalyzed coupling that traditionally uses far to much Pd as catalyst to be sustainable. We are working towards a new procedure, in water at ambient temperatures, which relies on ppm levels of catalyst. Allylations, such as those associated with indoles, are being pursued in addition to more traditional couplings based on diactivated methylene groups.

Biocatalysis

Along with the “new rules” that govern chemistry in water that utilizes micellar catalysis, it has been observed that these same nanomicelles formed by TPGS-750-M act as a “reservoir” for organic substrates and products formed from reactions based on bio-catalysis. That is, the micellar arrays present in the water provide a solubilizing alternative to both, minimizing their localization, and thereby blockage, of the enzymatic pocket. Ultimately, this leads to lower enzymatic inhibition, and thus, higher levels of conversion. Successful chemo- followed by bio-catalyzed sequences have been achieved in high overall yields and stereoselectivities, with up to (thus far) three steps being run in a 1-pot fashion. While these utilized alcohol dehydrogenase as the initial enzyme, additional families of enzymes are under active investigation.

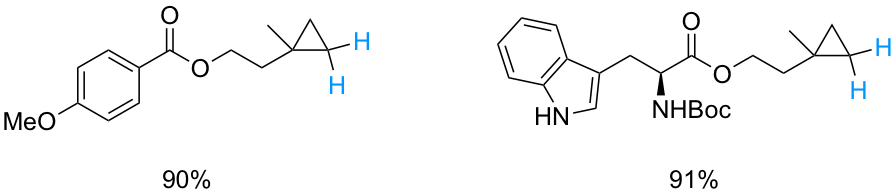

Ni-Catalyzed reductions of dihalocyclopropanes

New methodology is under development for the installation of cyclopropane rings onto organic frameworks, a particularly important transformation in the natural products area and among pharmaceutical companies, in particular. The majority of known methods involve reagents and/or conditions that are toxic, dangerous, environmentally deleterious, and reportedly non-scalable from an industrial standpoint. Our approach, however, involves generation of new ligated nickel nanoparticles capable of converting gem-dihalocyclopropanes to the corresponding cyclopropanes of interest via an environmentally friendly process, done in water under mild conditions. One example of such a conversion is shown below.

Flow chemistry

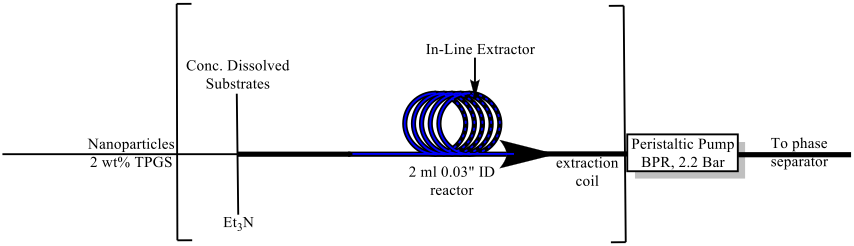

The introduction and adaptation of continuous manufacturing technologies to the laboratory setting has revolutionized the methods by which chemists can synthesize target compounds. Chemistry performed in ‘flow’ offers many advantages, such as: better universal heat control, improved mass transfer, safer handling of dangerous reagents, programmable and automated additions and separations, generally less waste, and reduced reactor footprint for scale-up applications, to name a few. Furthermore, flow reactors exhibit more versatility with respect to varying reaction type, notably for large scale purposes, as opposed to their batch counterparts. However, the use of aqueous based media in flow, where the solubility of both starting materials and products is low, has been woefully underutilized. Likewise, free-flowing catalysts traveling in-stream, i.e.,not in a packed column, also have presented significant challenges. Both components represent risk towards reactor clogging in-line, at switching valves and joints, and at back-pressure regulators. We have provided a solution that enables use of aqueous micellar catalysis, or use of just water containing varying levels of n-PrOH in a plug flow reactor system. We have also adapted this technology to a scalable continuously stirring tank reactor (CSTR) system where our Fe/ppm Pd nanoparticles can be applied as effective catalysts. As illustrated below, a system has been designed and used successfully for Suzuki-Miyaura cross-couplings, as well as aminations (i.e., C-N bond formations).

Total Syntheses

With today so many “tools in the toolbox” of green and sustainable technologies having been developed in the group, we have been applying these on a regular basis, targeting several drugs currently in use or that are in the pipeline undergoing clinical evaluation. Several of these are associated with health issues (e.g., malaria) that are found mainly in developing countries, where the prices of existing drugs are simply beyond the economic means of millions of residents. It is here where our approaches that utilize environmentally respectful chemistry translate into processes that offer a potentially lower cost bases for their manufacture. Thus, from both the environmental and fiscal perspectives, green chemistry always comes out on top. Why? Because when at scale organic solvents are no longer needed, from the standpoint of their purchase and, importantly, proper disposal, prices for doing synthesis drop. When the cost of investing energy due to reactions that require heating no longer exists, prices go down. And when the amount of a precious (or otherwise) metal catalyst is cut (e.g., by an order of magnitude, as in the case of Pd), this, too, can dramatically reduce the cost of a targeted pharmaceutical. These are the virtues associated with doing chemistry following Nature’s lead: in water.

What follows, therefore, are some of the drugs made recently in the group via total synthesis, closely following the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry. Many more syntheses are underway in the group, and will continue to be in the foreseeable future:

Interested in joining the group?

If you are considering joining us as a future graduate student, and you share the vision and have the passion to help change the world of organic chemistry, please let us know.